Review of HARRY HARRISON, HARRY HARRISON: A MEMOIR posted at SFSignal.com

My review of the late Harry Harrison’s memoir, appropriately entitled Harry Harrison, Harry Harrison, has been published on the two-time Hugo-award winning SFSignal.com.

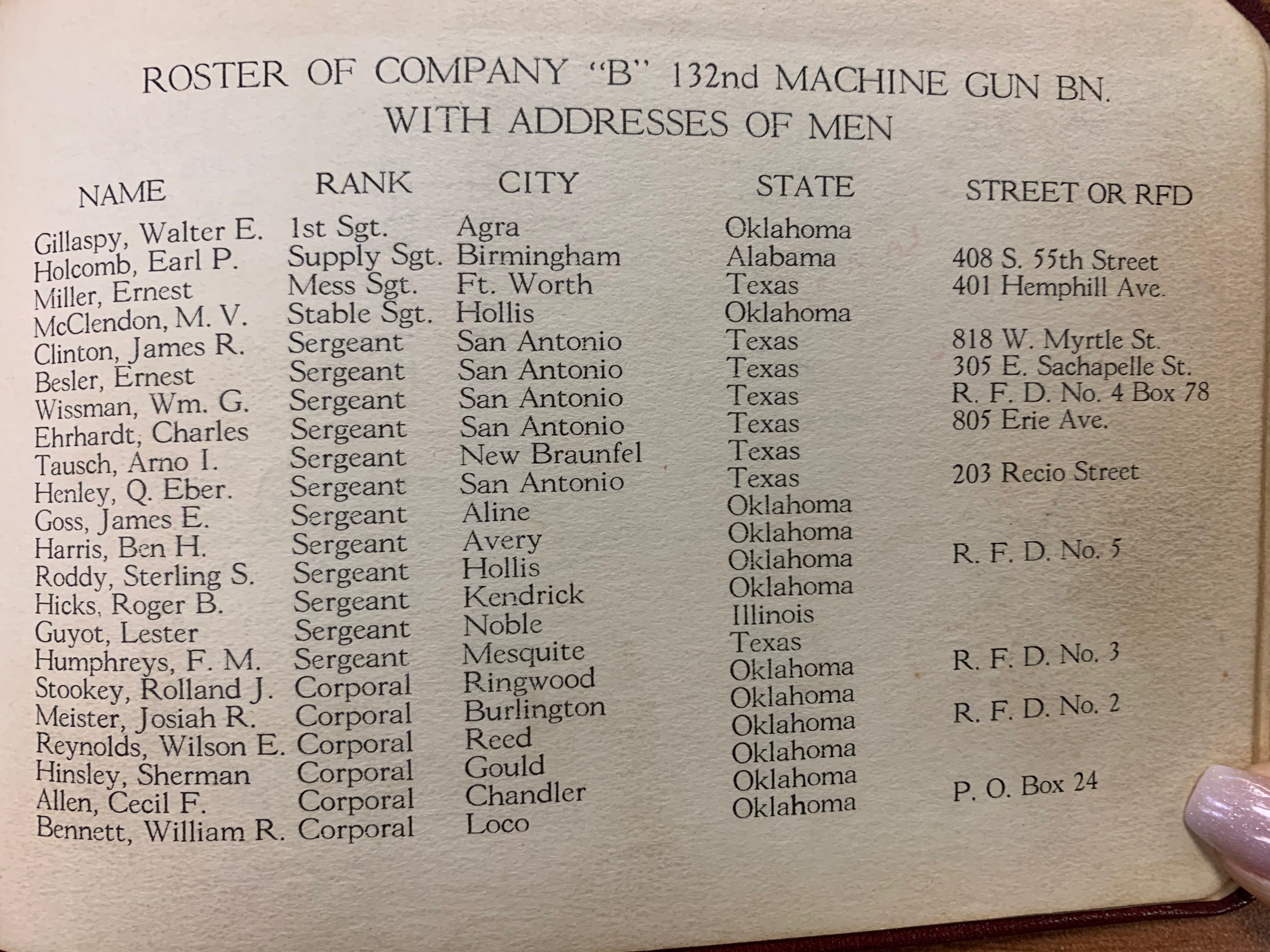

World War II veterans and early pulp fiction writers share a common timeline; they come from a common generation and most of them are slowly but surely passing from this earth. Born in the early 1920s, they went through the depression and then straight into World War II.

Harry Harrison (1925 – 2012), the author of Deathworld, Stainless Steel Rat, the West of Eden series and Make Room! Make Room! (which made into the movie Soylent Green) followed this path, was influence by it and then went off on his own path.

Born in Connecticut to a “mother from a family of Jewish intellectuals” and a father whose “family was middle-class immigrant Irish”, Harrison and his family lived through the Depression in and around New York City.

I was shielded from the rigors of grim necessity; there was always food on the table. However I did wear darned socks and the same few clothes for a very long time, but then so did everyone else and no one bothered to notice. I was undoubtedly shaped by these harsh times and what did and dod not happen to me, but it must not be forgotten that all of the other writers of my generation lived through the same impoverished Depression and managed to survive. It was mostly a dark and grim existence; fun it was not. (pg 34)

Harrison’s novel Bill, The Galactic Hero demonstrates his dislike of the military, and his memoir echoes that sentiment. Though he never saw combat (spending most of his WWII years at a gunnery range near Laredo), he still learned to hate military life.

Harrison’s novel Bill, The Galactic Hero demonstrates his dislike of the military, and his memoir echoes that sentiment. Though he never saw combat (spending most of his WWII years at a gunnery range near Laredo), he still learned to hate military life.

My life at the time was quite boring in content and can be summed up quite easily. It was the same as every other draftee of my generation. We grew up, starting as teenagers, and ending as army adults perfectly adjusted to military life. We learned to curse constantly, to chase girls when we got a pass to town – and to avoid work whenever possible. I could now fieldstrip a caliber .50 in the dark, could drive a truck – double-shifting the clutch, now a lost art – had hear untold live rounds fired on the ground gunnery range where I ended up – and have been deaf ever since. (pg 65)

Harrison used his GI Bill money to attend art school and began illustrating comics and science fiction. He was one of the founders of the Queens Science Fiction Club, keeping close to the genre.

After being discharged and living in NYC for a short time, Harrison had the audacity/fearlessness/cajones to leave the comfy confines and English speaking world of the US and live in Mexico, Denmark and Italy with a young family, in his quest to become a full time writer. His philosophy on life (it seemed like a good idea at the time) and writing helped cope with these times when money and other essentials may have been scarce:

A word of sage advice for any young writers: hock the bourgeois gear. Art comes first. If you are not committed completely you do not deserve to succeed. Harsh but true. (pg 147)

Harrison and family (with baby Todd) were in Italy when their resolve for this type of life was tested.

We now reached the bottom moment, the blackest night we had ever experienced. This moment came when we were down to exactly sixteen cents – one hundred lire. The price of one more airmail stamp to my agent or a liter of milk for Todd. These are the kind of moments in life one really does not need, but we had walked into it with our eyes wide open. Making this decision had been much harder for Joan than me. I had known that I wanted to write, needed to write, had stories and books that needed doing. I hoped that I would succeed. Joan did not hope. She felt very secure in her knowledge that I would do these things, create art, create literature – and support our family with earned income. I had no such assurance – she was rock steady in her belief. She had put everything on the line and would not waver. So she solved this one as well. Since I wasn’t doing too well as a good provider, she realized she had to go out and do it herself. She talked to the two brothers who ran the grocery store. In Spanish-Italian, she convinced them that it would be a wise thing to extend us credit. An acknowledgement to her tenacity, and their kindness. This was done. (pg. 147-148)

The memoir piece of this book sputters to a halt around the 1970s, with some brief vignettes that cover the next few decades. My assumption is that this part had to be cut short due to Harrison’s illnesses toward the end of his life. Some of these vignettes cover “not writing porn” (“I didn’t join the Silverbergs and Malzbergs and all the others who wrote porn back then.”), organizing the first World SF conference in Ireland in 1976, and other snapshots.

However, several essays are added to this memoir that were to be integrated are included, and, IMHO, they are worth the price of admission (yeah, okay, this is an ARC, so a low price of admission for me, but you get the drift).

The essays included as Part II would be worth the read as stand alone efforts. They cover a wide range of topics and Harrison’s most well-known works/series. The essays are:

The essays included as Part II would be worth the read as stand alone efforts. They cover a wide range of topics and Harrison’s most well-known works/series. The essays are:

- John W. Campbell – “When I was fifteen years old I thought John W. Campbell was God!” This essay includes great descriptions of lunches with Campbell as he rattles off ideas, and Harrison’s idea to film with James Gunn (who had grant money) lunch with Campbell.

Real evidence of the dubiety of the screenplay was driven home to me when I overheard Edward G. Robinson say to the director, “Dick, I read the script and I don’t understand my role.” With good reason: there was nothing there to understand. Summoning up my courage, I introduced myself and offered to provide answers about his character. He ignored my rudeness, invited me to lunch with him, then listened closely while I explained the character he played as I had visualized him in the book. “You are the only person in this film who has lived in the world the we know now, who has seen a world of plenty. He can survive in this world of pollution, overpopulation and chronic food shortages. That doesn’t mean he has to like it.” Robinson said: “That’s a very good idea. Why didn’t they tell me? It isn’t in the script.” (pg 275)

- Esperanto – first exposed while in the service in Laredo, Harrison was a big supporter of this world language.

- Russia – Harrison’s Russian agent says to him “Harry, I don’t know how to tell you this, but you are the most popular author in Russia, and also the most stolen!”

- Stainless Steel Rat

- West of Eden

- Alternate History

The book contains a detailed timeline of Harrison’s life and a detailed bibliography.

This review is based on an Advanced Reader Copy sent to SF Signal.