Svalbard – Close to the Top of the World

After a day and a half in Copenhagen, we flew by way of Oslo, Norway to Longyearbyen, on the archipelago of Svalbard. Like us, you may be asking “Where the heck is Svalbard?”. To answer that pressing question, below is a photo of an excellent map found at the North Pole Expeditions Museum in Longyearbyen. I’ve cropped it and added some annotations for context.

This cool map is looking at the world from the top. The North Pole is at 90 degrees north latitude. I’ve marked the line for 85 and 80 north, plus some other countries for orientation. The Svalbard archipelago is highlighted in green.

This was the farthest north we’ve ever been, and probably will ever be. Not quite 80 degrees north, but the cruise ship going and coming to Ny-Ålesund passed 79 degrees north. The Svalbard archipelago exists between 74 and 81 degrees north.

Longyearbyen

We had two nights in Longyearbyen, the port where we would board our Hurtigruten cruise. The airport had one of the coolest direction signs ever, complete with glaciers in the background and the ever-present polar bear warning sign.

The polar bear signs surround the city (and every city in Svalbard) to warn/remind people not to venture past them without a rifle. Said weapon is to be used to scare off any polar bears. We did not view a polar bear at any distance at any place during this trip, as they had all retreated north to colder climes (we visited during August). But we did see lots of these signs!

Longyearbyen is the Northernmost settlement with a permanent population over 1,000 (source). Formerly a whaling and mining community, the main industries now are research and tourism.

Waking up early one morning there (due to jet lag and the midnight sun) I hiked up one of the hills that surrounded the city and took a panoramic video. And yes, I stayed within the confines of the polar bear signs.

We went Dog Sledding without snow with a company named Green Dog, and had an enjoyable time with the dogs. You can read a separate article on that adventure here.

We visited two museums in Longyearbyen: the North Pole Expeditions Museum and the Svalbard Museum. The North Pole Expeditions museum was a small but jam-packed set of items, photos, movies and letters about the race to the North Pole. Most of these expeditions started from Svalbard, many from the next stop in our journey, Ny-Ålesund. The museum had a ton of information on Norwegian Roald Admunsen and on the Italian Norge dirigible and its inventor/pilot Nobile. More about that later in the Ny-Ålesund section.

At the Svalbard Museum, Audrey got an up close encounter with a polar bear – as close as she wanted to be.

Longyearbyen is also home to Svalbard Brewery. I partook of their brews all over town – and they had them on the cruise ship as well (Dark Season and Gruve3 beers were outstanding!). For a small community, the city had several restaurants that we really enjoyed. Our first dinner was at Kroa where among other items we tasted the smoked minke whale and homemade moose burger under the watchful eye of Roger.

One location we did not go to was the Global Seed Vault, mainly because there are no tours (one can simply stare at the front of the building) It, like many places, were outside of the polar bear safety zone. I would have hiked all over the area if possible, as there were what looked to be some very cool hikes but all were outside of the polar bear signs.

Ny-Ålesund

Our first stop after boarding the ship in Longyearbyen was further north to the town of Ny-Ålesund. It is and was a mining town, but also was the departure place for several blimp attempts to reach the North Pole. Our visit was in August, but the wind was blowing and we heat-accustomed Texans felt it was quite cold – with amazing scenery.

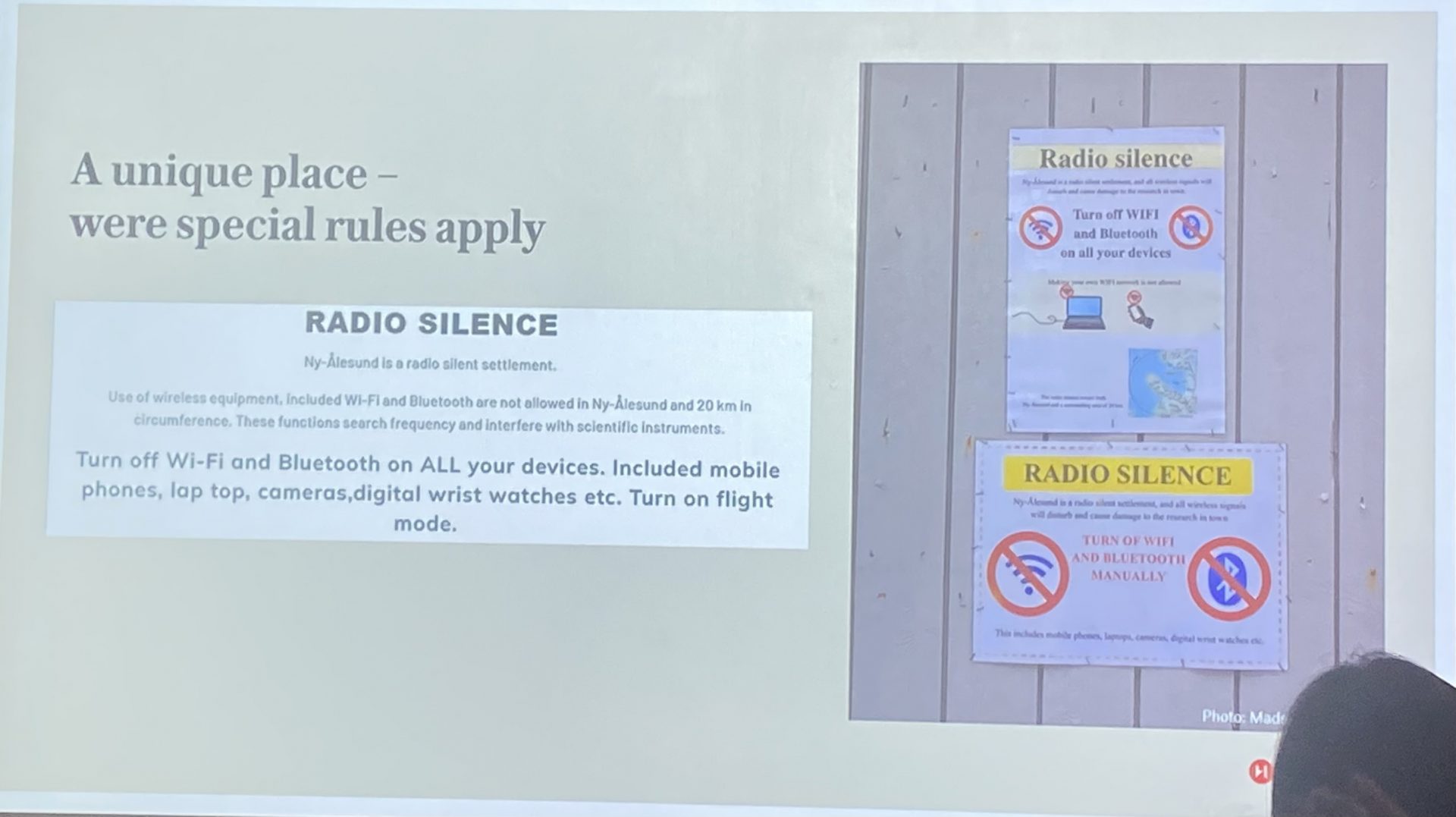

We had been told that the ship Wi-Fi (and all devices with WiFi and Bluetooth) would be turned off as we approach the town. This because “these functions search frequency and interfere with scientific instruments”. And, promptly about 30 minutes out, the WiFi shutdown and the announcement was made to the entire ship.

Ny-Ålesund has the world’s northernmost post office (we did not have anything to mail, unfortunately – but we did take a photo!).

It also had one very cool Arctic Fox pup that Audrey caught a great picture of. We were told that it was one of a litter of four.

The town is, like Longyearbyen, the site of mining, tourism and research. Many of the buildings we walked by on the short loop around the town were research sites.

This sign had a map that showed where in the hills beyond it some of the mines had existed.

Ny -Ålesund was also the starting point for many attempts to fly over the North Pole. The Norwegian Roald Amundsen has a statue here, as he was the leader of a good number of those attempts. Some were successful, some were tragic.

To paraphrase what I read and what was told to us, Amundsen was a Norwegian explorer who explored the Northwest passage and both poles. He was heading for the North Pole, heard the claims that Peary and Cook had reached there first, and not wanting to be second, decided to head for the South Pole (Peary and Cooks claims have fallen under scrutiny) He and his team were the first to reach the South Pole. He then returned his attention to the North Pole. After several attempts by plane, he decided to try airships (blimps, dirigibles, zeppelins…so many names!). He decided to use an airship called Norge from an Italian named Umberto Nobile. They did indeed reach the North Pole. Nobile made other attempts, during one his airship crashed and many search parties were sent to find and rescue Nobile and his team. One such party was lead by Amundsen in a sea plane. The plane when down somewhere in the Arctic waters and was never recovered.

That’s my short version. But I much prefer the longer versions below, which were found on the placards in the North Pole Expeditions Museum. If you want to skip this detailed history section, thank my wife for this idea and click or tap here.

Roald Amundsen was a Norwegian explorer born in 1872.

He participated in his first expedition to Antarctica with a Belgian expedition in 1897.

He set off for the Northwest Passage in 1903 with the ship Gjoa and six crew members where they successfully arrived at Nome, Alaska, in 1906.

Amundsen started to think about The North Pole, but in 1909 he discovered that Robert Peary and Frederick Cook both claimed to have reached it. Instead, he secretly started to plan an expedition to The South Pole with the polar ship Fram.

In January 1911 the Fram arrived in Antarctica, and a base camp was established at the Bay of Whales in the Ross Sea. In October 1911, Bjaaland, Hanssen, Hassel, Wisting, and Amundsen departed with four sledges and 52 dogs. On 14th of December 1911, Amundsen and his party reached the South Pole where they raised a tent and named the camp “Polheim” (“Home on the Pole”).

In 1918, Amundsen started another expedition with the polar ship Maud. He wanted to navigate the Northeast Passage. Although the Maud expedition did not reach The North

The possibility of attempting to reach The North Pole was remote until Lincoln Ellsworth

Ellsworth was financing the first try with the Italian sea-planes Dornier-Wal N24 and N25 flying towards the North Pole in 1925 Unfortunately, they did not reach the Pole because the planes remained damaged on the pack ice.

They reached 88 degrees North.

from the poster “Roald Amundsen” from the North Pole Expeditions Museum

Amundsen, Ellsworth, Riiser-Larsen and Dietrichson decided, after the attempts in 1925, that it was better to go to the North Pole by airship instead of plane.

Nobile was one of the foremost experts in airships at that time, and the airship N1 was a semi-rigid construction designed by himself.

It measured 106 m in length, 24.3 m in height and 19.6 m in width. The rubber envelope encased 19 500 m3 of hydrogen gas and the frame was of duralumin. There were three Maybach engines, each of 245 hp, and the keel was open so that the crew could move between the gondola (cabin) beneath the huge gas envelope and the engines and attend to all exterior parts of the airship.

The airship was perfect for such a mission. Nobile could also give assurances of the acceptance of the Italian government for the purchase of the N1.

The considerable finances for the expedition were secured in three ways, as reflected in the final name of the expedition: Lincoln Ellsworth again gave a large sum, the Italian government gave an important sponsorship and the Norsk Luftseiladsforening (Norwegian Air Navigation Society) chipped in as

The principal actors of this expedition were Roald Amundsen, Lincoln Ellsworth, Umberto Nobile, Rolf Thommessen (Norsk Luftseiladsforening), Hjalmar Riiser-Larsen, and Leif Dietrichson.

from the poster on “the airship Norge” from the North Pole Expeditions Museum

Umberto Nobile was born on January 21st, 1885, in Lauro, a small town not far from Naples. He studied electro-mechanics and industrial engineering and after that, he worked mostly on engineering and aeronautical projects.

Expert of aerostatics he became Director of the Military Aeronautical Construction Works (S.C.A.). Nobile succeeded in securing several important orders to Italy from foreign countries which acquired his airships and accessory technologies. He had gradually transformed his airships from military use to transport of goods and passengers.

In 1922, Nobile worked in Ohio as a technical consultant on the construction of the semi rigid military airships for the “Goodyear Corporation”. In 1923, he returned to Italy and continued working on the “N1” airship which turned out to be a technical success. In test flights it attained a speed of 115 km/h with engines of only 750 hp.

He was not only working for Italy. At the same time, he was supervising the construction of several other airships for Great Britain, United States, Spain and Argentina. He is the inventor of the “Mr”, the minimum reduced, a special airship of 1040 cubic metres, the smallest ever built that represents an outstanding technical achievement because of its original design and splendid flight performances.

from the poster “Umerto Nobile” at the North Pole Expeditions Museum

We were able to walk out to the mooring pole used for one of the airships. This was beyond the polar bear safe area.

As denoted in the plaque attached to the morning tower, Amundsen, Ellsworth and Nobile did fly across the North Pole in the airship in 1926.

Nobile and others tried again in 1928 (either once was not enough, or Nobile felt that Amundsen was getting all the credit?), with disastrous results.

In June 1928 the Latham 47 was tasked to help search for the airship Italia. The French Government made the hydroplane available to Roald Amundsen.

The crew was composed by Renè Guilbaud, Albert Cavalier de Cuverville, Emile Valette, Gilbert Brazy, Leif Dietrichson and Amundsen.

On the 18th of June, Latham left Tromse and continued towards Spitsbergen.

Ingoy Radio communicated with Latham 47 answering an inquiry about the ice conditions around Bear Island. Shortly thereafter radio communication went silent. This was the last time anyone heard anything from Latham 47.

After the Latham 47 disappeared, many Norwegian and French boats searched for the missing crew and the plane. These ships were searching around Bjornoya (Bear Island), the eastern coast of Spitsbergen, and between Greenland and Svalbard along the sea ice edge.

there was found a pontoon, identified as the wing of the Latham 47, and a fuel tank that determined to be Latham 47’s forward internal fuel tank.

Subsequent modification of the tank may indicate that survivors had attempted to use the tank as a float, perhaps as a substitute for the pontoon that had been torn off.

Amundsen’s disappearance was a national tragedy for Norway.

from the poster “Latham 47” at the North Pole Expeditions Museum

During our time viewing the mooring tower and the plaque, we were guarded by another young lady with a gun. I asked her if they had any recent sightings and she said they had seen one on one of the close islands in the last few days.

And, the obligatory polar bear warning sign photo – this one in English!

As we walked back to the ship, admiring the view, a seal started jumping out of the water. He or she can be found as the dark spot in middle of the photo below, with the nice blue glacier in the background.

Ny-Ålesund was a small town, we were only there for a couple of hours. But it was obviously full of history. Back on our ship, we were off for a full day at sea, and then to the top of Norway (and, as it were, the top of the European continent).