TSHA’s Texas Almanac – historical data science analysis

The data scientists in my company Media Sourcery have been using Tableau to analyze various types of data from our products and our customers. In recent projects with the Texas State Historical Association (TSHA), I’ve been exposed to the wealth of historical data that is contained in their systems, particularly in the Texas Almanac.

The data scientists in my company Media Sourcery have been using Tableau to analyze various types of data from our products and our customers. In recent projects with the Texas State Historical Association (TSHA), I’ve been exposed to the wealth of historical data that is contained in their systems, particularly in the Texas Almanac.

TSHA is working toward a digital redesign, the next step in the continuing evolution of the data and content that make up the Almanac, the Handbook of Texas, the Historical Quarterly, and other properties. This redesign project will not only better integrate the data between the different digital publications, but prepare it for more types of reusability, such as using much of the data for further analysis projects. And, as always, this data is readily and easily available.

What follows is a step by step guide to merge data science and the historical Texas data that is in the Texas Almanac, as an example of how this data can be utilized. The concept of utilizing data science concepts on historical data certainly isn’t new (see fellow TSHA Board Member Andrew Torget’s outstanding list of Digital Historic projects as an example) but with the availability of data from respected sources such as the TSHA and tools like Tableau Public (which is free) there are little to no barriers to entry.

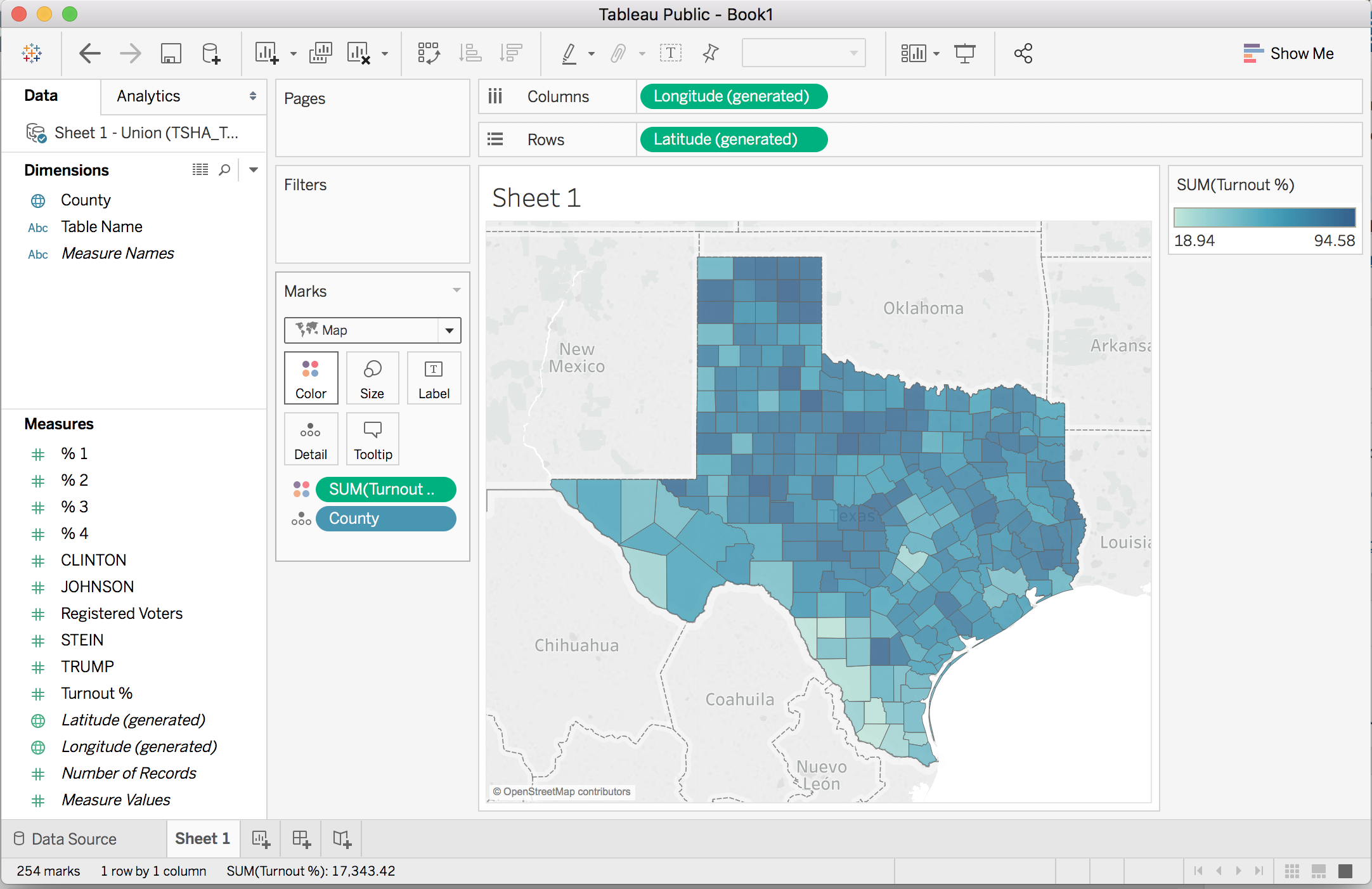

This is my first Tableau project, and I made several mistakes along the way (which I’ll share). The current results are below. This is an embedded Tableau view. You can click on it, then click on the different counties to see percentages.

Step 1 – Download the latest Texas Almanac

Anyone can download a PDF version of the latest Texas Almanac here. You can also sign up to be a member of the TSHA on the same page.

Step 2 – Use the downloaded PDF file of the Almanac as a Data Source in Tableau

If you don’t already have Tableau, the public version can be downloaded here.

To connect to the PDF, select “PDF File” under “Connect” and then navigate to and select the downloaded Texas Almanac PDF file.

Step 3 – Pick a set of tables

There are A LOT of PDF tables in the Almanac. I chose one mostly at random from pages 459 – 463 to build a map of relative voter turnout in the most recent Presidential Election. Since it was such a close election, I wondered if the turnout would be high, and how the turnout varied from county to county.

I also wanted to find one that was a bit complicated, mainly to show that most problems encountered can be overcome.

These tables go from pages 459 to 463. Tableau will scan the entire PDF and find all of the tables in that file if you want. But I just entered the page numbers for the tables I wanted.

Step 4 – Let Tableau Clean the Data

In the box on the left, Tableau shows the tables it found. These are indeed all of the tables for all of the counties. To make them into one big table, Tableau has the “Union” feature. This can be used for more complex linkages between separate tables, but we simply want all of these tables into one table with the same column headers.

This is the first point where I had to try a couple of different avenues. I attempted to do a Union with all of the tables. The number of tables that the Tableau scanner found on page 462 was 2; but if you look at the screenshot a couple of steps ago, there is clearly only one table.

To perform a union, double-click on “New Union” and drag all of the tables into the box that appears. After you do this, the columns below are show in the data window. Because of the layout of the tables in the PDF document, specifically that there are two lines of header columns, the different tables are read in as having different column names (e.g., all of the “F1”, “F2”, etc. column names). This could be cleaned up by showing the data (clicking the “Update Now” button) and merging the columns that should be together.

Notice the checkbox that says “Cleaned with Data Interpreter” in the left column right under the labels “Tables” in the Tableau Desktop. This feature attempts to clean up the data before it presents it. After checking that box, three new “cleaned tables” appear in the list of “Tables” (scroll down to see them). From the original PDF, there should be only one table per page. By dragging the two original tables on pages 459 and 460 (which apparently didn’t need cleaning) and the three cleaned tables, the Union dialog looks like the next screenshot.

After hitting “ok”, there are still more columns that there should be, but most of them have labels. The Data Interpreter even identified the column “County” as containing geographical data (note the “globe” icon at the top of the column).

Step 5 – Filter and Merge

Click the “Update Now” button and the data pulled from the tables is shown.

The first row shows “Statewide” data, where all of the other data shows county-level data. This needs to be filtered out. In the upper right, under the label “Filters”, click “Add” and follow the instructions to Add a filter for field “F1” (this is the first column name); select the entry for “Statewide” and check the “exclude” box (i.e., exclude the row that contains the entry “Statewide” in the column named “F1”.

The column “F1” is now County data, but it has not been identified like the “County” column as geographic data. We can fix that by clicking on the “Abc” label over the F1 column, selecting “Geographic Data” and “County”.

If we scroll down in the data, to the F1 entry “Fayette” (which is also the last entry in the table from the first page of the PDF we scanned), we see that the county name for the next entry “Fisher” is not in column F1 but in column “County”.

The Data Interpreter was unable to match these columns. Tableau provides a mechanism to merge columns. Highlight the columns labeled “F1” and “County” (on a MAC hold the “command” key down and click on both columns), then right-click on one of the two columns and select “Merge Mismatched Fields”.

This could be done for all of the columns, but I’m only interested in County, Registered Voters and Turnout %, so I only merged those columns. I then right-clicked on the labels and renamed them.

If you scroll to the top of the data, you can see that since we merged the F1 and County column and renamed it, the filter we added was removed. That filter can be added back in repeating the steps we went through above, this time on the newly renamed “County” field.

Step 6 – Make the Map

Now that we have County data, click on “Sheet 1” at the bottom left of the screen to start plotting the data.

On the left, the data is now separated into “Dimensions” and “Measures”. This screen allows us to plot measures like “Turnout %” against dimensions like “County”.

Drag “County” from the Dimensions section to the blank area under “Marks”….and we finally have a map of Texas.

Click the drop-down under “Marks” and select “Map”. Now some, but not all of the counties are filled in.

Determining what was causing some of the counties to not have data displayed stumped me for a while. I checked the data table for errors, tried to see if all the missing ones were alphabetical, and attempted many other diagnosis.

The cause is that some county names are the same as county names in other states. Tableau needs to be told these counties are all for Texas. In the top menu, select “Map”, then “Edit Locations…”. Then it shows several counties as “Ambiguous”. Select the great state of Texas as the state in the “Fixed” drop down, and now our map is full.

Step 7 – Add the data

Highlight the “Turnout %” entry under the “Measures” section, and drag it to the color area under “Marks.” Now we’ve added data to the map. Clicking on a county shows the county name and turnout percentage.

Unfortunately, as you can see below, there is a problem. The data says that one of the data points claims a voter turnout percentage of 7,803…which is quite impossible unless everyone voted 78 times (and a few voted more!). An examination of the PDF show that the entry for Kendall County (which is the one marked below in dark blue) has a comma instead of a decimal in the percentage. Using the Tableau Data Interpreter didn’t fix this issue.

But of course, all is not lost. We have our data cleaned almost the way we want it. There are no options to edit the PDF data (at least not that I can find), but we can export to a CSV file, fix the problem data and re-import. We can then go through these same steps again (now that we know how to do them).

Step 8 – Export to CSV

Click on the “Data Source” tab at the bottom left of the screen to get back to the data area. Then in the top menu click “Data”, then “Export Data to CSV File”. Save the file to a location you’ll remember.

Step 9 – Edit the data

Open the CSV file with Excel or Numbers (on Mac). I went ahead and deleted the row that had the entry “Statewide” (so that we would no longer have to filter it) and changed the comma in the Kendall County row for turnout percentage to a decimal point. The file now should be saved as a Microsoft Excel file, as Tableau has a connection option for those files.

Step 10 – Connect to the Excel file and go through the steps again

In the top menu, click on “Data”, then “New Data Source.” Similar to Step 2 above, connect to your data source – which this time is the Excel file from Step 9. The data in the Excel file comes up, but with the column names in the data. If you again click the “Cleaned by Data Interpreter” as in Step 4, Tableau will read the column names correctly and take them out of the data.

Since the data was cleaned and merged before it was exported to CSV file, several of the previous steps can be skipped. Proceed from Step 6 until the map shows all of the counties, and the “Turnout %” numbers are shown for each county.

Step 11 – Clean Up the Map

There are several additional tweaks that can be done to clean up the map:

- Click above the map where it says “Sheet 1” and add a title.

- In the top menu, click “Map”, then “Map Layers”. Uncheck the boxes for country names, state names and state boarders. This will bring the focus to the Texas Counties.

- Also under “Map”, select “Map Options” and turn off the Map Toolbar.

Step 10 – Publish

In the top menu, under “File,” select “Save to Tableau Public.” This publishes the maps on the Tableau Public servers, and allows them to be utilized as they have been here in this article. Depending on website type, the map views can be added to websites via embedded links or iframes. The view below is uses the iframe option.

There are several future directions that can be taken with this map and data, such as adding data from past almanacs. A very high percentage of the past Texas Almanacs have been scanned in and are available.

Hopefully this has been helpful. I would appreciate hearing pointers from any data scientists on making this process clearer. If any readers are interested in working with Texas historical data, there are lots to access on the Almanac website; let me know if you have a specific project or need help finding data.

And please consider becoming a member of the wonderful Texas State Historical Association.

Thanks to Frank de la Teja and my lovely wife Audrey (as always) for the read-throughs, suggestions and editing.

[poet-badge]